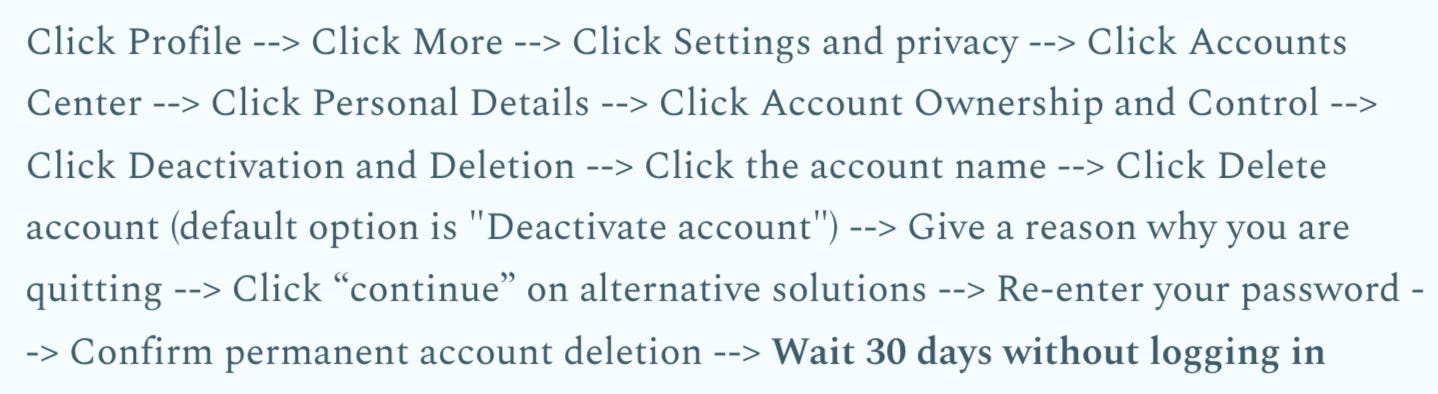

Compulsive social media usage is now considered a behavioral addiction, similar to gambling (HBR). I have felt this addiction as well, but found comfort in knowing I could delete my account if it ever got too much. Last year, the day came when I felt that the harm Instagram was causing my mental health was greater than the benefit, and so I decided to delete my account. After going through Instagram’s 16-step program, I received the following instructions: Wait 30 days without logging into your account for the deletion to be completed. Oh, and if you log in at any point, we will stop the deletion and reset the counter.

“You can cancel the permanent deletion process at any time […] by logging in to your Instagram account”.

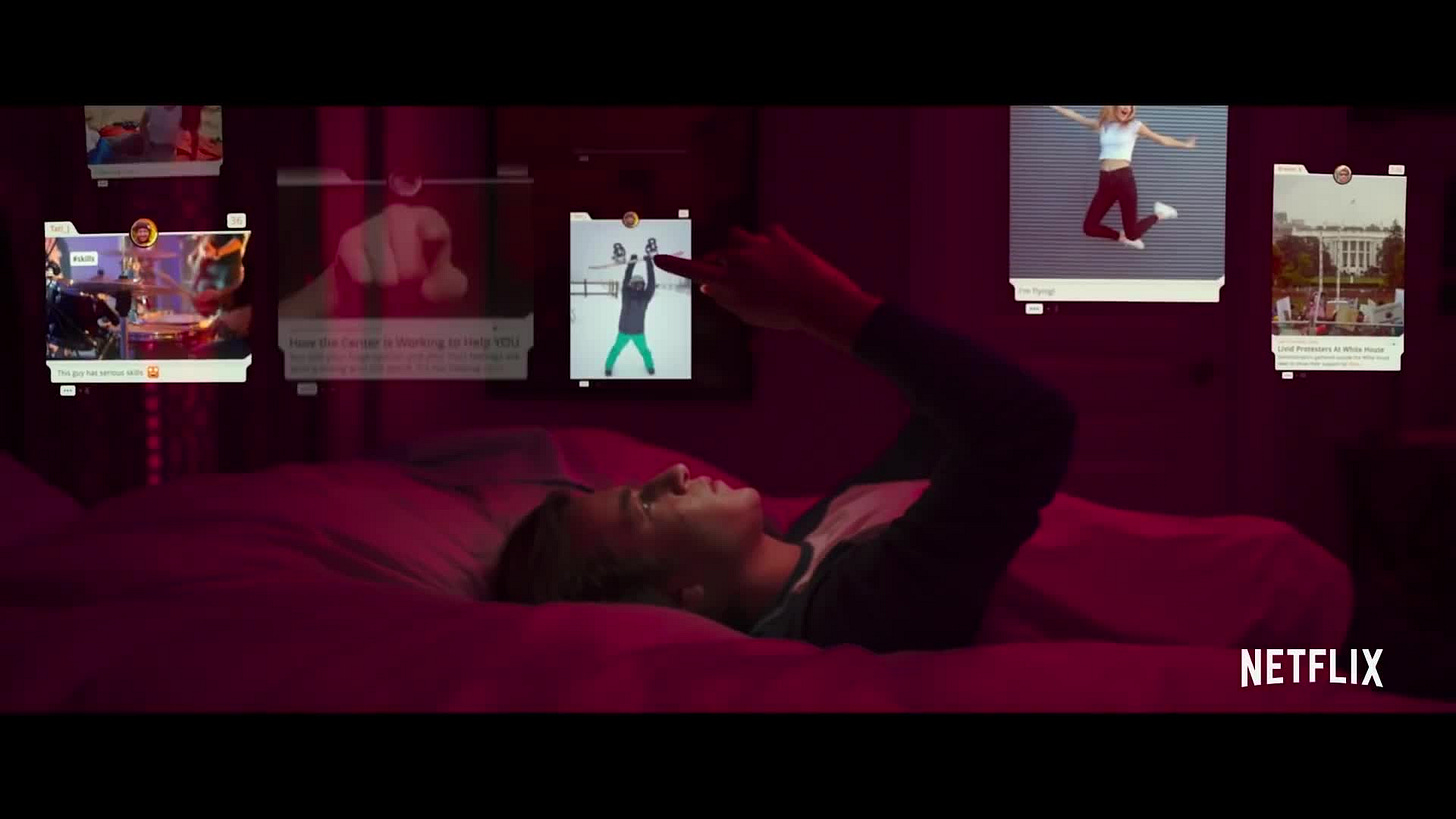

Quitting social media is difficult as it is. A survey this year found that 85% of respondents interact with social media “mindlessly”, and 45% have attempted and failed to reduce their social media usage. As addictive behavior is often involuntary, I might habitually click into my account despite my conscious intentions. Even if I delete the app, the web client is only a click away. We have laws around gambling that put high barriers to entry to dissuade people from engaging with the activity. In social media, we see almost the opposite: There is a high barrier to quitting. So, in this blog, I ask the question: Why is it so difficult to delete my Instagram account?

16 Clicks and 30 Days

First, the empirical evidence. Let’s compare the steps required to perform two actions on Instagram: Deleting your account and watching a video. As of October 2023, it takes 16 clicks and a month-long wait to delete your instagram.

In comparison, here is the 1-step guide to watching a video on Instagram: Click Reels, and the video autoplays.

While I find the 16 steps excessive, we can read some of the barriers charitably. Asking me whether I would like to deactivate my account may save me from more work down the line. Asking me to confirm my intention to delete my account three times may ensure that I do not accidentally trigger the action. A 30-day wait may give me enough time to revert the decision if someone hacked into my account while I was on vacation (in a magical world where people don’t check their Instagram on vacation). But, with all my charitable reading, I cannot find a way to make sense of this line: “You can cancel the permanent deletion process at any time […] by logging in to your Instagram account”.

Dark Patterns and Hostile Design

Many technologies are hard to interact with due to poor design, but some technologies intentionally make deceptive design choices that manipulate users into engaging with platforms in ways that they do not want to, called “dark patterns”. This particular dark pattern is called Hard to Cancel: "making the cancellation process overly complex and time consuming, [causing] users to give up trying to cancel”. But we have grown used to dark patterns in software technologies, so instead, I want to make an analogy to hostile design, a related concept from architecture that shows the insidious possibilities design can enable.

Whereas most technologies are designed to perform a function, some are built defensively, to make it difficult to perform a function. An example is Robert Moses, the urban planner who designed most of New York City in the 20th century. Notoriously, Moses designed bridges around Long Island too low for busses to pass under. The decision could be shrugged at as poor design, but the justification was more pernicious than careless. Low bridges forced public transport busses to avoid the roads under them, ensuring that low income (and mostly Black) residents of New York City did not have a way of reaching the pristine beaches of Long Island. (BBC) Moses’ bridges made transportation harder, not easier, for certain groups of people.

Proving Intent

It is difficult to prove Moses’ intentions without going into his personal beliefs, but as STS scholar Langdon Winner shows, the impact of hostile design is the same regardless of intentions. When technologies are built with such asymmetric incentives, they "transcend the simple categories of intended and unintended altogether". Their impacts are mostly invisible to their daily users; public transport users accept that busses simply doesn’t go to Long Island beaches. But regardless of whether or not Moses intended to exclude poor and Black New Yorkers from reaching pristine beaches, the impact is the same. Similarly, regardless of whether or not Instagram intends to encourage users to continue mindless engagement with the platform, the impact is the same.

That said, we also have leaked internal documents and whistleblower statements that show intent. Here is Meta’s founding president: “How do we consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible? [...] We’re exploiting a vulnerability in human psychology.” Here is its former VP of Growth: “So we want to psychologically figure out how to manipulate you as fast as possible and then give you back that dopamine hit. We did that brilliantly at Facebook. Instagram has done it. WhatsApp has done it.” Here is leaked internal research conducted by Meta: “We [Instagram] make body image issues worse for one in three teen girls”.

Conclusion

When you decide to watch a video on Instagram, this is an action Instagram incentivizes, so it only takes one click. When you decide to delete your Instagram account, suddenly your goals diverge from that of the platform. Naively, we hope that the playing field is leveled, but by engaging in dark patterns and hostile design, the social media platform gets the upper hand. Plainly, subtle design decisions push us to behave in ways that we don’t want to.

The “evil social media” trope is well known to us, but we mostly choose to ignore it. If you are like me, part of you may be holding on to the belief that you have some choice in the matter — you can leave the platform when you get sick of it. (ie: I can quit whenever I want). But addictive substances and behaviors target human neurochemistry in ways that make it an uphill battle to quit. With a 30-day waiting period and the attached kill switch, Instagram makes it even harder to quit, pushing against the user’s desires. Edward Tufte, a design professor, famously said: “There are only two industries that call their customers 'users': illegal drugs and software”. Indeed, the neighborhood drug dealer tends to be quite friendly when the user goes to make their first purchase, but much less so when they say they want to quit. The convenience you demanded is now mandatory.

Been a while since I deleted ig and found myself on substack. This was a great read, thank you!

It's funny, i purposely opened substack this morning instead of IG to keep from scrolling. Congrats on deleting ✨